Staying at Home wasn't Safer

Published in the Boulder Daily Camera, 5/31/20

In the era of coronavirus, we are desperate for the wisdom of scientists to help us live safely. Maybe the most vexing current question is how to safely emerge from lockdowns. They are new to our modern world so little is known and any scientific evidence that illuminates what strategies do and don't work helps.

On April 27th, Governor Polis allowed Colorado counties to adopt "Safer at Home" policies that significantly reduced lockdown restrictions. When several Northern Front Range counties chose not to follow his lead, this offered up a practical science project that shed light on the best way to escape from lockdowns.

Two counties – Douglas and Larimer – adopted the Governor's Safer at Home rules while six other counties – Boulder, Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield, Denver, and Jefferson – chose to continue the "Stay at Home" policies for another 12 days sustaining stricter limits on their citizens' movement and rights to gather and work.

At the heart of their decision, the six Stay at Home counties sacrificed an increased freedom to move, gather, and work for better health outcomes. But, now that it's behind us, did these counties' policies result in any observed health benefits? That’s a science question and, by training and experience, I'm a scientist. I knew the State of Colorado had data that might answer this question.

On April 27th I began I tracking the daily number of cases reported in all six northern Front Range Stay at Home counties as well as in the two Safer at Home counties. I sought help from an old college buddy, Dr. Chris Papasian, a Professor Emeritus and epidemiologist at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, School of Medicine who has served on hospital infection Committees for many years. With his guidance, I was able to use Colorado's data to search for health benefits in the counties that Stayed at Home.

The first issue I had to resolve was how to compare the coronavirus case data across different counties with different populations and demographics. Besides county population differences, there are other known factors that influence the risk of coronavirus infection including the ages of the residents, population density, and the number of currently contagious individuals, to name but a few. Finding a way to fairly compare the counties knowing there were differences in their citizens' vulnerability to the disease was essential.

Considering our options, Dr. Papasian suggested that the best option available to factor in county vulnerability was to adjust new county case data based upon the total number of coronavirus cases that the county had experienced prior to April 27th. So, for each day studied, I divided the number of new daily coronavirus cases in each county by the total number of cases the county had experienced through April 27th. Changes in this measure would more fairly characterize how well a county's strategy was working to reduce the likelihood of its residents catching the disease.

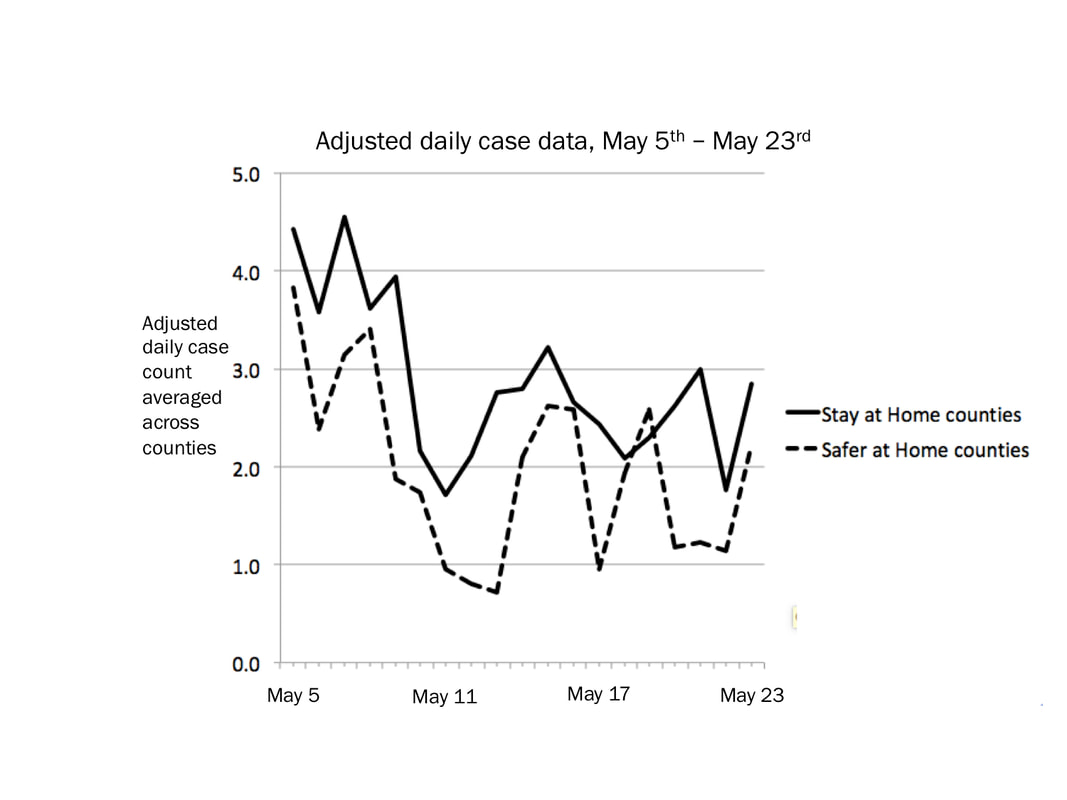

Timing of the data was also an issue. On April 27th, the county policies diverged, but on May 9th county policies converged again, as Stay at Home Counties adopted the Safer at Home policies. After exposure, it takes one to two weeks for symptoms to emerge. So, case data from April 27th – May 4th represented only people exposed to the virus before the county policies diverged and, as such, wasn't relevant. During the two weeks after May 9th (when county policies converged again), the new case data included individuals exposed while the county polices differed. So, the period between May 5th and May 23rd, which is the data I analyzed, represents a window of time where the daily case data included infections that developed while the counties were following different policies.

What did the data tell us? The accompanying chart presents the daily adjusted average case data for May 5th through May 23rd for the Stay at Home vs. the Safer at Home counties The smaller the number, the better the health. This chart tells us two things.

In the era of coronavirus, we are desperate for the wisdom of scientists to help us live safely. Maybe the most vexing current question is how to safely emerge from lockdowns. They are new to our modern world so little is known and any scientific evidence that illuminates what strategies do and don't work helps.

On April 27th, Governor Polis allowed Colorado counties to adopt "Safer at Home" policies that significantly reduced lockdown restrictions. When several Northern Front Range counties chose not to follow his lead, this offered up a practical science project that shed light on the best way to escape from lockdowns.

Two counties – Douglas and Larimer – adopted the Governor's Safer at Home rules while six other counties – Boulder, Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield, Denver, and Jefferson – chose to continue the "Stay at Home" policies for another 12 days sustaining stricter limits on their citizens' movement and rights to gather and work.

At the heart of their decision, the six Stay at Home counties sacrificed an increased freedom to move, gather, and work for better health outcomes. But, now that it's behind us, did these counties' policies result in any observed health benefits? That’s a science question and, by training and experience, I'm a scientist. I knew the State of Colorado had data that might answer this question.

On April 27th I began I tracking the daily number of cases reported in all six northern Front Range Stay at Home counties as well as in the two Safer at Home counties. I sought help from an old college buddy, Dr. Chris Papasian, a Professor Emeritus and epidemiologist at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, School of Medicine who has served on hospital infection Committees for many years. With his guidance, I was able to use Colorado's data to search for health benefits in the counties that Stayed at Home.

The first issue I had to resolve was how to compare the coronavirus case data across different counties with different populations and demographics. Besides county population differences, there are other known factors that influence the risk of coronavirus infection including the ages of the residents, population density, and the number of currently contagious individuals, to name but a few. Finding a way to fairly compare the counties knowing there were differences in their citizens' vulnerability to the disease was essential.

Considering our options, Dr. Papasian suggested that the best option available to factor in county vulnerability was to adjust new county case data based upon the total number of coronavirus cases that the county had experienced prior to April 27th. So, for each day studied, I divided the number of new daily coronavirus cases in each county by the total number of cases the county had experienced through April 27th. Changes in this measure would more fairly characterize how well a county's strategy was working to reduce the likelihood of its residents catching the disease.

Timing of the data was also an issue. On April 27th, the county policies diverged, but on May 9th county policies converged again, as Stay at Home Counties adopted the Safer at Home policies. After exposure, it takes one to two weeks for symptoms to emerge. So, case data from April 27th – May 4th represented only people exposed to the virus before the county policies diverged and, as such, wasn't relevant. During the two weeks after May 9th (when county policies converged again), the new case data included individuals exposed while the county polices differed. So, the period between May 5th and May 23rd, which is the data I analyzed, represents a window of time where the daily case data included infections that developed while the counties were following different policies.

What did the data tell us? The accompanying chart presents the daily adjusted average case data for May 5th through May 23rd for the Stay at Home vs. the Safer at Home counties The smaller the number, the better the health. This chart tells us two things.

First, the slight but noticeable slope downwards of the lines for both the Stay at Home and Safer at Home counties tell us that daily coronavirus caseload was in decline over the period. There was no evidence whatsoever of any resurgence of the virus in any of the eight counties studied. New coronavirus cases decreased over the 12-day period regardless of differences in restrictions between counties.

Second, in every day but one of the nineteen days studied, the two Safer at Home counties had better observed health outcomes than the Stay at Home counties. But, hold off on the champagne if you think this is evidence that less restrictive social-distancing policies will improve health outcomes. Many additional factors that could not be considered because of the limitations of the state's data could explain these results. We know that contagious diseases spread through social contact. More social contact will never reduce the spread of a contagious disease. Rather, what these findings tell us is that the Safer at Home policies recommended by the Governor proved to be a safe and low risk strategy that worked as planned.

The bottom line is that the additional restrictions associated with the Stay at Home policies kept in place for 12 additional days by the six counties had no observable positive effect on the health of those counties' residents.

In fairness, the county governments that chose the more restrictive Stay at Home behaviors for their citizens did so to protect their health from an evolving threat that is poorly understood. However, going forward, we should learn from our mistakes as well as our successes. This bug is deadly so we should proceed with caution at every step. However, the race is not just against the disease – it's increasingly against society's need to get out from under lockdowns where the wisdom of Amazon's Jeff Bezos also applies, " being wrong might hurt you a bit but being slow will kill you."

Second, in every day but one of the nineteen days studied, the two Safer at Home counties had better observed health outcomes than the Stay at Home counties. But, hold off on the champagne if you think this is evidence that less restrictive social-distancing policies will improve health outcomes. Many additional factors that could not be considered because of the limitations of the state's data could explain these results. We know that contagious diseases spread through social contact. More social contact will never reduce the spread of a contagious disease. Rather, what these findings tell us is that the Safer at Home policies recommended by the Governor proved to be a safe and low risk strategy that worked as planned.

The bottom line is that the additional restrictions associated with the Stay at Home policies kept in place for 12 additional days by the six counties had no observable positive effect on the health of those counties' residents.

In fairness, the county governments that chose the more restrictive Stay at Home behaviors for their citizens did so to protect their health from an evolving threat that is poorly understood. However, going forward, we should learn from our mistakes as well as our successes. This bug is deadly so we should proceed with caution at every step. However, the race is not just against the disease – it's increasingly against society's need to get out from under lockdowns where the wisdom of Amazon's Jeff Bezos also applies, " being wrong might hurt you a bit but being slow will kill you."